Differential Treatment Response of Proactive and Reactive Partner Abusive Men: Results from a Laboratory Proximal Change Experiment

[La respuesta al tratamiento diferencial de hombres maltratadores proactivos y reactivos: los resultados de un experimento de cambio proximal de laboratorio]

Julia C. Babcock1, Sheetal Kini2, Donald A. Godfrey1, and Lindsey Rodriguez3

1University of Houston, TX, USA; 2The Lighthouse Arabia, UAE; 3University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA

https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2024a2

Received 18 September 2022, Accepted 9 October 2023

Abstract

Objective: The current study reexamines data from Babcock et al. (2011) proximal change experiment to discern the differential utility of two communication skills-based interventions for proactive and reactive partner violence offenders. Method: Partner violent men were randomly assigned to the Editing Out the Negative skill, the Accepting Influence skill, or to a placebo/timeout and reengaged in a conflict discussion with their partners. Proactivity was tested as a moderator of immediate intervention outcomes. The ability to learn the communication skills, changes in self-reported affect, observed aggression, and psychophysiological responding were examined as a function of proactivity of violence. Results: Highly proactive men had some difficulty learning the Accepting Influence skill and they responded poorly to this intervention. They responded positively to the Editing Out the Negative technique, with less aggression, more positive affect, and lower heart rates. Low proactive (i.e., reactive) men tended to feel less aggressive, more positive, and less physiologically aroused after completing the Accepting Influence technique. Conclusions: This study lends support for tailoring batterer interventions specific to perpetrator characteristics.

Resumen

Objetivo: El presente estudio reexamina los datos de Babcock et al. (2011) con respecto a un experimento de cambio proximal para discernir la utilidad diferencial de dos intervenciones basadas en habilidades de comunicación para agresores de violencia de pareja proactivos y reactivos. Método: A los agresores se les asignó aleatoriamente a las condiciones habilidad de eliminar lo negativo, habilidad de aceptación de la influencia, o placebo/tiempo fuera y volvieron a participar en una discusión conflictiva con sus parejas. Se evaluó la proactividad como moderadora de los resultados proximales de la intervención. Se examinó la capacidad de aprender habilidades de comunicación, los cambios en el afecto autoinformado, la agresión observada y la respuesta psicofisiológica en función de la proactividad de la violencia. Resultados: Los hombres muy proactivos tuvieron algunas dificultades para aprender la habilidad de aceptación de la influencia y respondieron escasamente a esta intervención. Sin embargo, respondieron positivamente a la técnica de eliminar lo negativo, con menor agresión, más afecto positivo y una frecuencia cardíaca más baja. Los hombres poco proactivos (es decir, reactivos) tendían a sentirse menos agresivos, más positivos y menos activados fisiológicamente después de completar la técnica de aceptación de la influencia. Conclusiones: Este estudio proporciona apoyo a la adaptación de las intervenciones para maltratadores a las características específicas del agresor.

Keywords

Battering intervention, Intimate partner violence, CouplesÔÇÖ interactions, Observational coding, Treatment matchingPalabras clave

Intervenci├│n con maltratadores, Violencia de pareja, Interacciones de pareja, Codificaci├│n de la observaci├│n, Coincidencia en el tratamientoCite this article as: Babcock, J. C., Kini, S., Godfrey, D. A., and Rodriguez, L. (2024). Differential Treatment Response of Proactive and Reactive Partner Abusive Men: Results from a Laboratory Proximal Change Experiment. Psychosocial Intervention, 33(1), 43 - 54. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2024a2

Correspondence: jbabcock@uh.edu (J. C. Babcock).

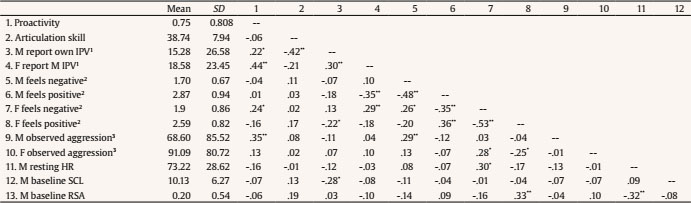

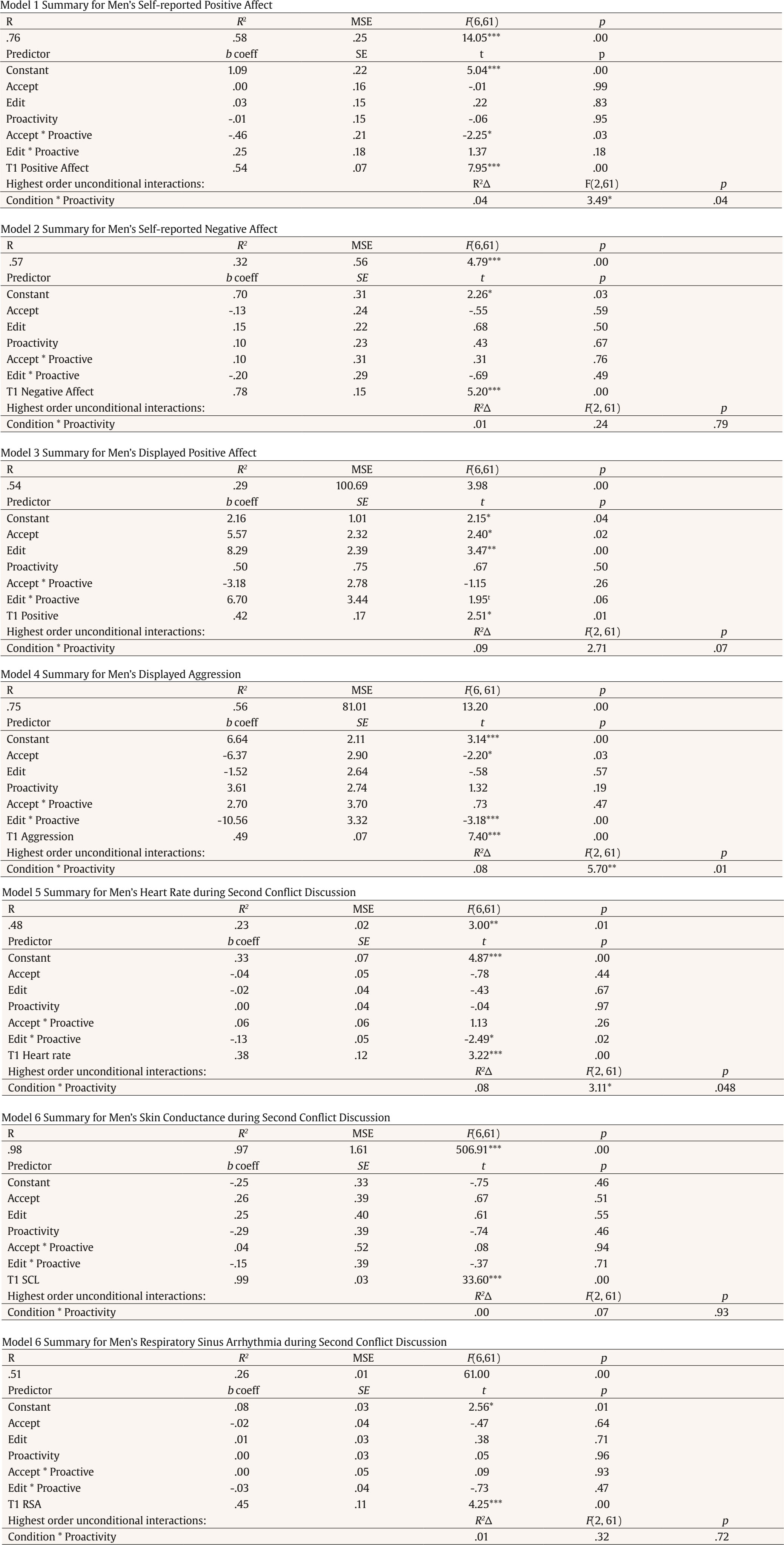

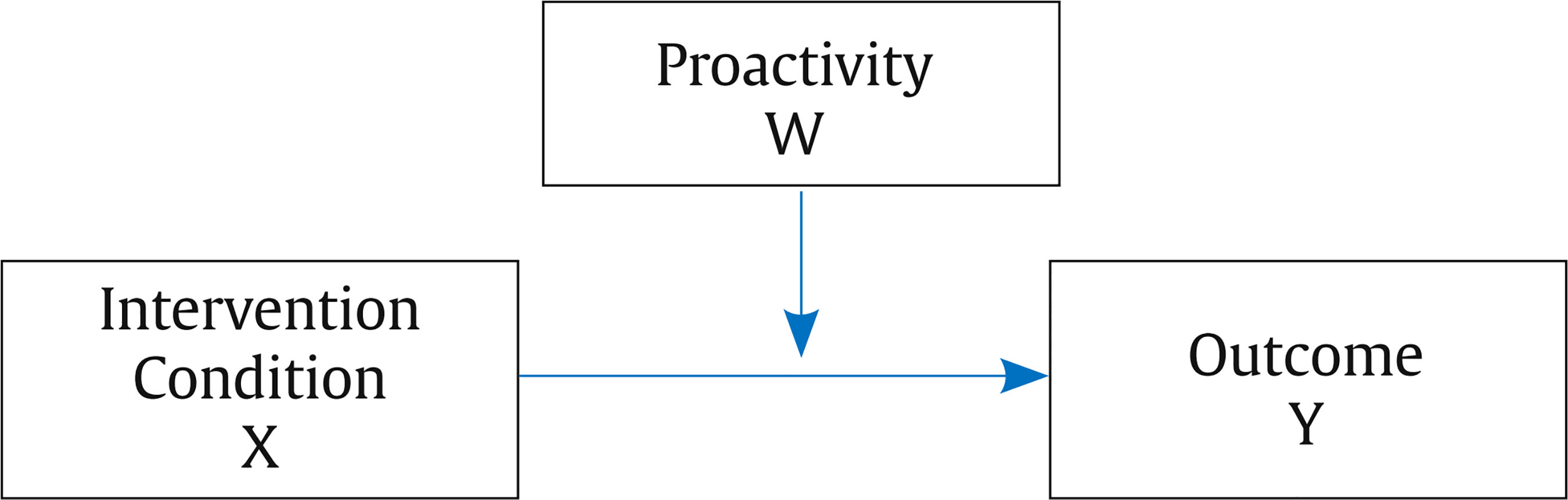

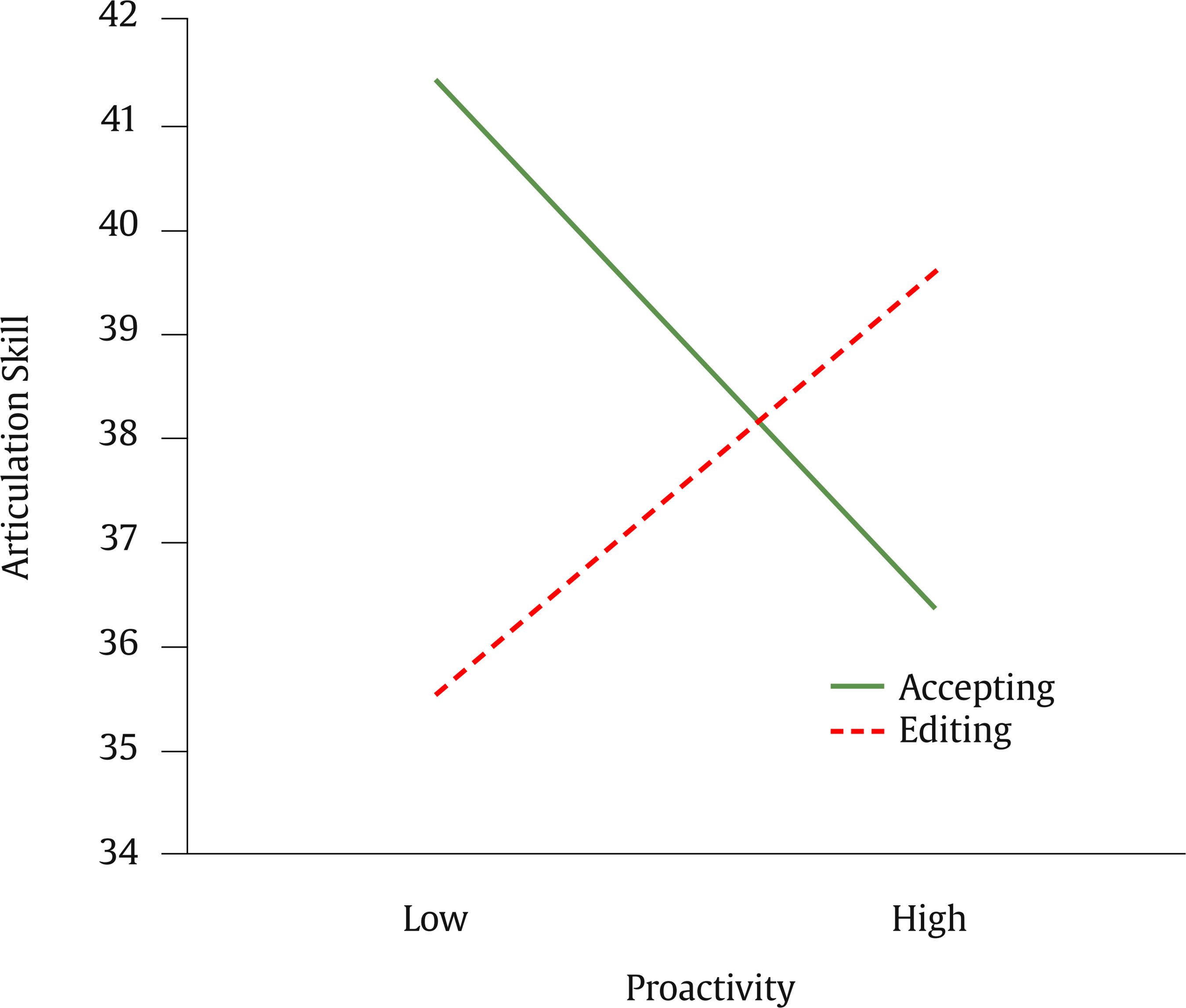

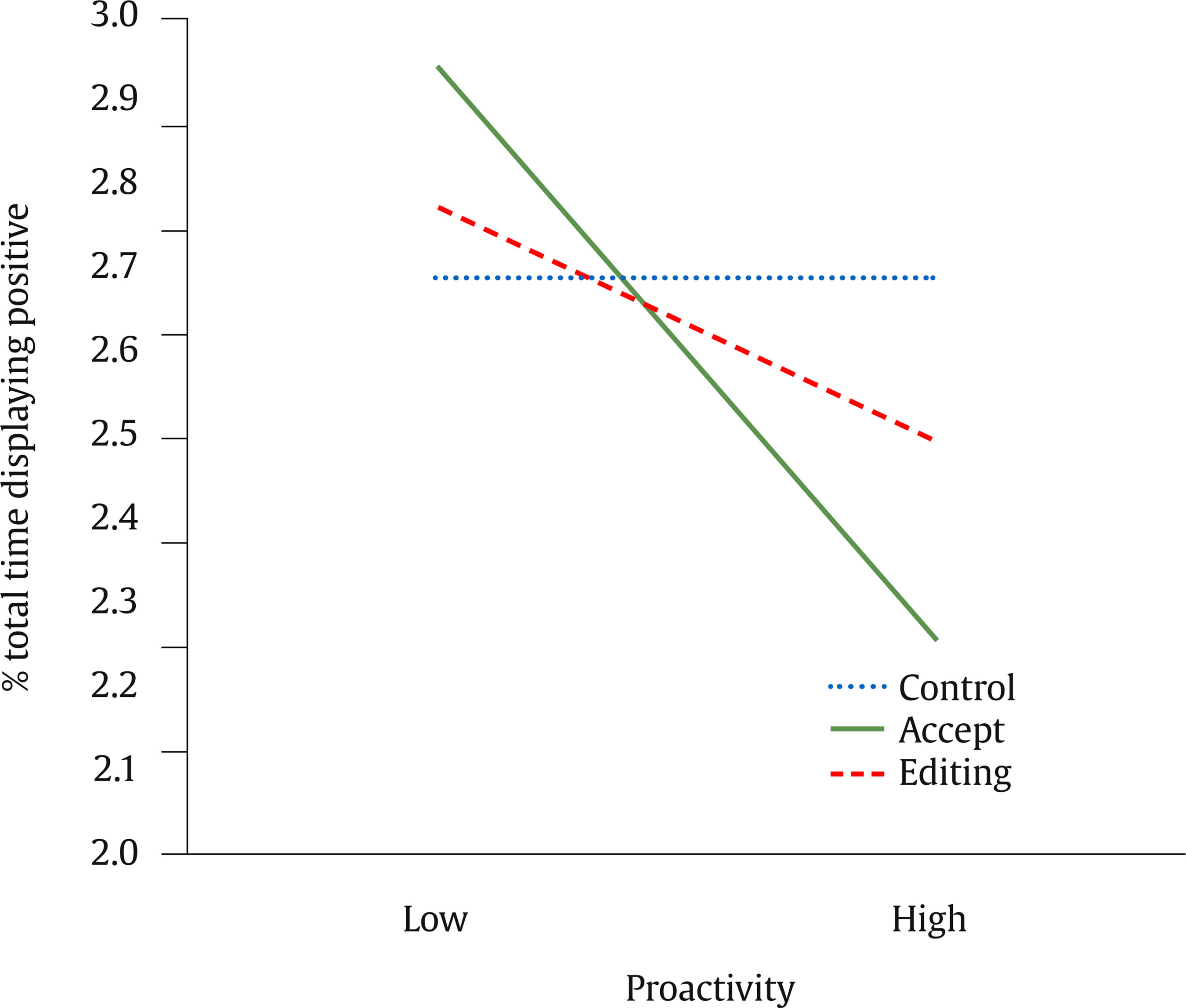

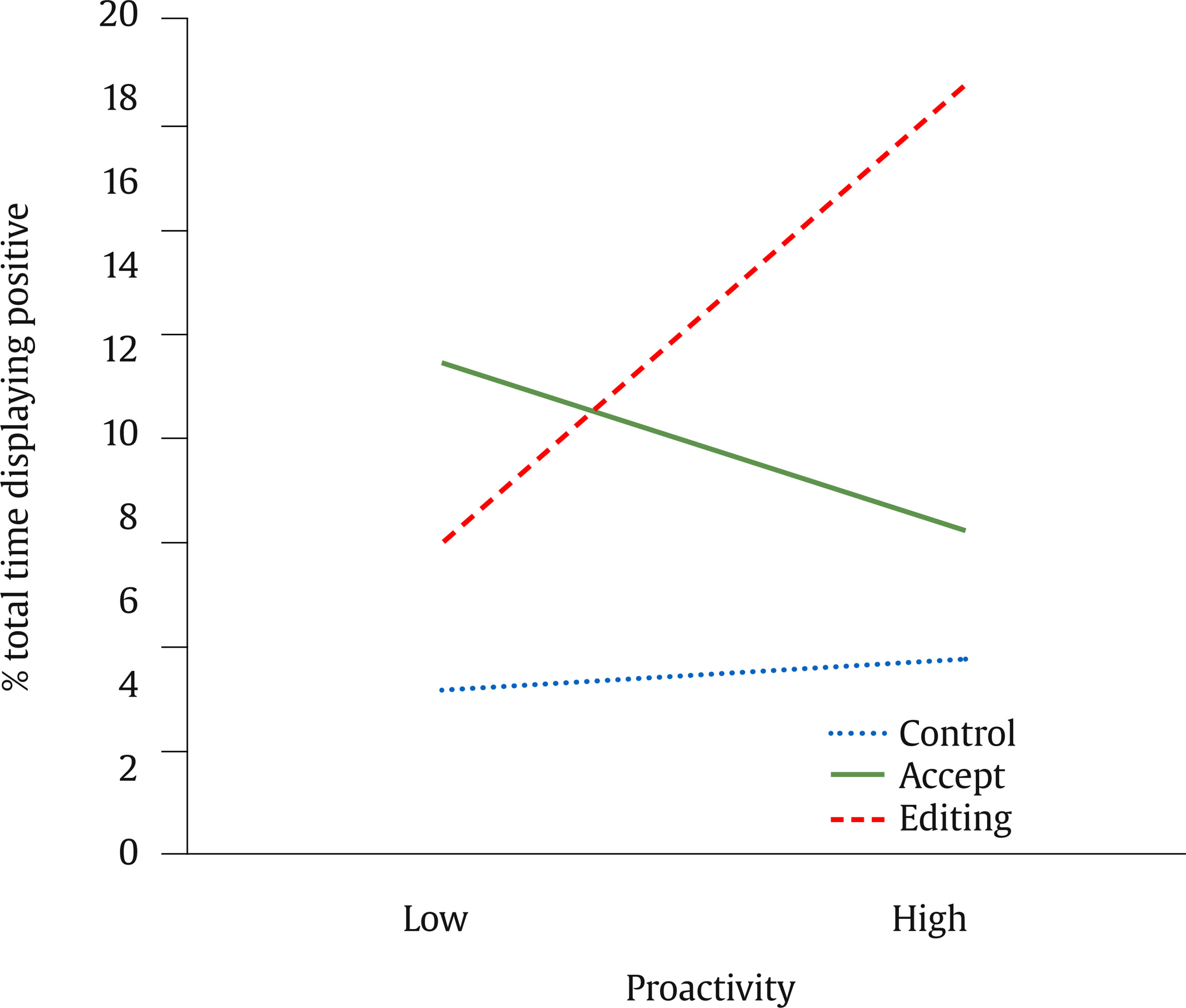

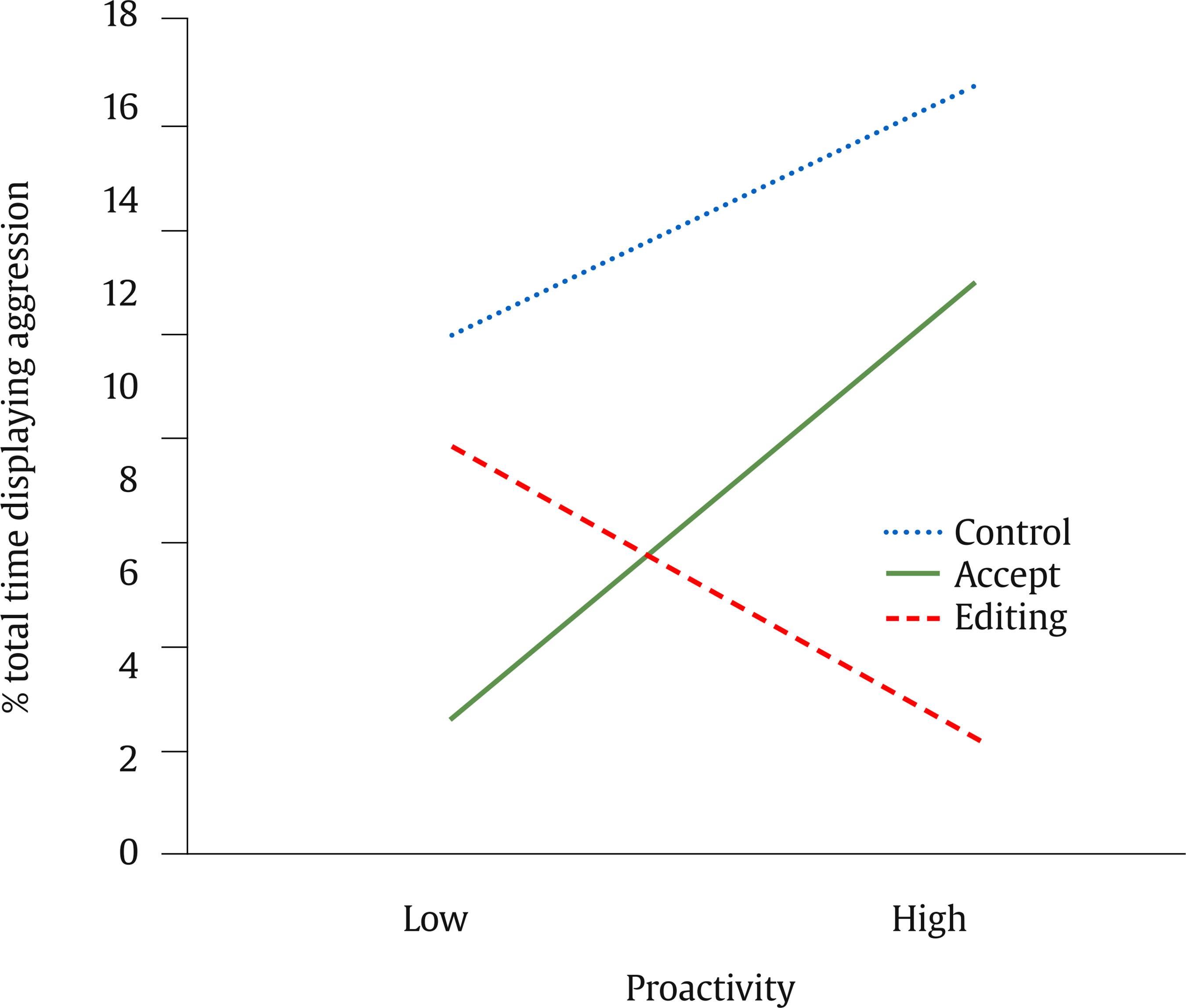

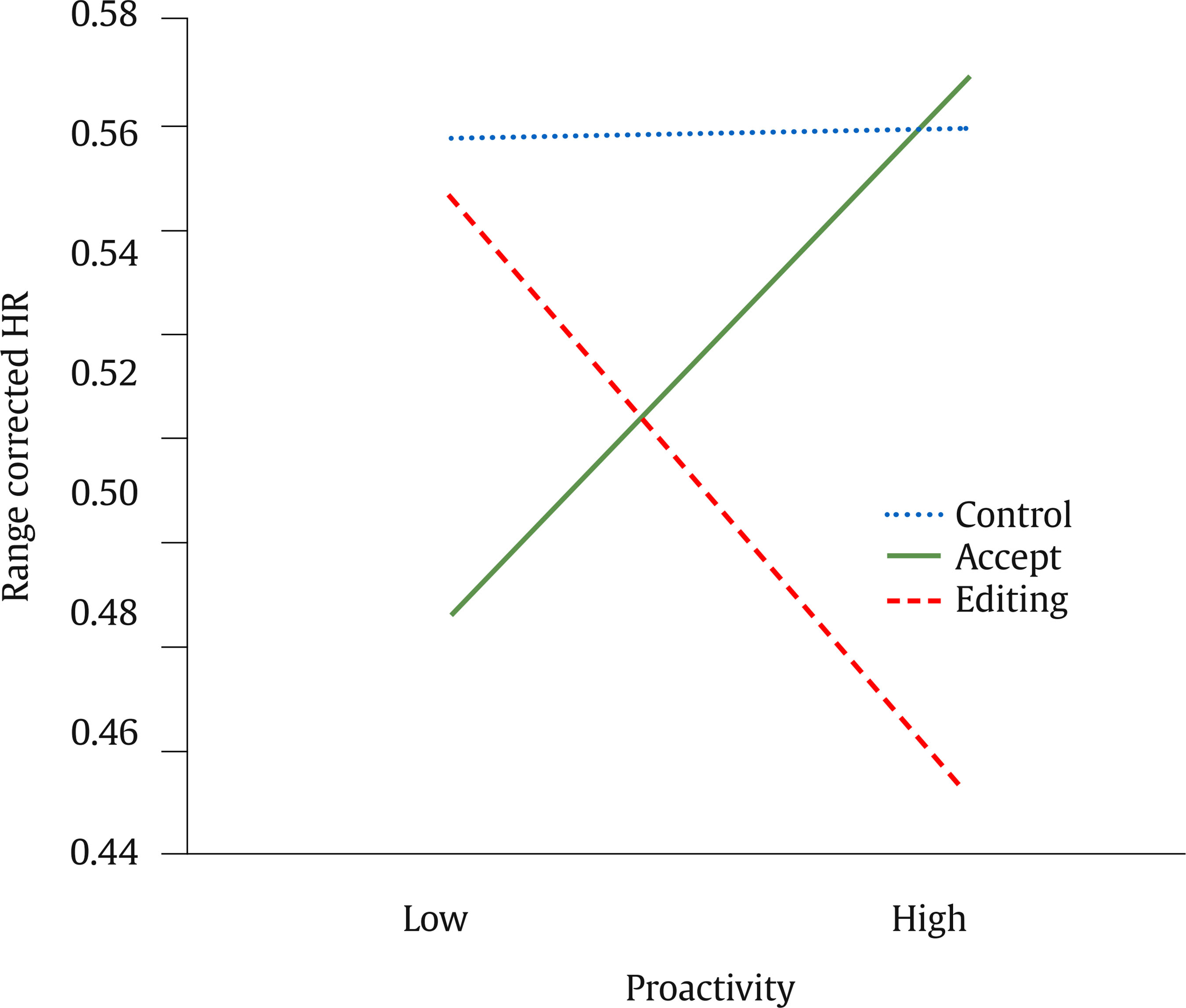

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is an international epidemic, with approximately 27% of women having experienced some type of IPV (physical or sexual, or both) by their male partners during their lifetimes (Sardinha, et al., 2022). In the United States, IPV affects nearly 12 million people each year, costing approximately $5.8 billion USD annually. Although court-mandated battering intervention programs “offer great hope & potential for breaking the destructive cycle of violence” (US Attorney’s, 1984 Task Force), historically they have not been highly effective (Babcock et al., 2004; Eckhardt et al., 2013; Travers et al., 2021). It is noteworthy that, although intimate partner violence often arises from arguments that escalate out of control, typical group interventions for IPV do not address men’s communication skills. Moreover, battering interventions are generally applied indiscriminately to men arrested for domestic violence regardless of the factors perpetuating their violence (Babcock et al., 2004). However, this ‘one size fits all’ approach to battering interventions is a significant limitation (Babcock et al., 2016; Healey, 1999). One way to improve outcomes may be to match treatment strategy to different types of perpetrators. Researchers have proposed a variety of different typologies over the decades to classify men who batter women on common characteristics, such as personality disorder features, (Holtzworth-Munroe & Stuart, 1994; Saunders, 1992), heart rate reactivity (Gottman et al., 1995), and proactive-reactive violence (Babcock et al., 2023; Chase et al., 2001; Walters, 2020). The proactive-reactive dichotomy attends to antecedents and motivations for violence, capturing the context in which the violence occurs. The proactive-reactive typology of aggression has been widely applied to samples including violent youths (e.g., Dodge & Coie, 1987; Merk et al., 2005; Raine et al., 2006), psychiatric patients (Nolan et al., 2003), forensic samples (Muñoz et al., 2007), and perpetrators of IPV (e.g., Chase et al. 2001; Ross & Babcock, 2009; Tweed & Dutton, 1998). While reactive aggressive tendencies predict more serious violence recidivism in the general criminal population (Walters, 2011), only proactive tendencies moderate the link between past and future violence among IPV samples (Walters, 2020). Reactive aggression, also called impulsive, unplanned, hostile, expressive, affective, and hot-blooded (Ramirez & Andreu, 2006), occurs in response to perceived provocation and in the presence of high arousal and anger (Bushman & Anderson, 2001). Reactive violence involves impulsivity, self-defense from a perceived threat, and high autonomic arousal (Puhalla & McCloskey, 2020). A reactive IPV offender may respond aggressively during high states of arousal, feeling provoked or pulled towards aggression by, for example, a perceived insult from his partner or the threat to break up (Babcock et al., 2000; Chase et al., 2001). Autonomic nervous system (ANS) hyper-reactivity, as measured by increased heart rate, increased sympathetic arousal, often measured through skin conductance (sweating), and decreased parasympathetic soothing, often measured through respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA), is thought to be associated with reactive aggression (Armstrong et al., 2019; Murray-Close et al., 2017; Puhalla & McCloskey, 2020). Their violence was thought to be reactive, unplanned, a result of anger, physiological flooding, abandonment fears, or emotional dysregulation (Babcock et al., 2005). Proactive aggression, also referred to as instrumental, premeditated, predatory, planned, and cold-blooded (Ramirez & Andreu, 2006), is enacted without provocation, and in the absence of anger (Merk et al., 2005) or high autonomic arousal (Raine et al., 2006; Ramirez & Andreu, 2006; Thomson et al., 2021). Proactive violence is intentional and instrumental, that is, violence motivated by obtaining an ulterior goal, like control, compliance, or submission (Babcock et al., 2014; Chase et al., 2001). For example, the proactive violence of an IPV offender may serve as a means of intimidating or controlling his partner or for getting his own way when conflict arises (Ross & Babcock, 2009). ANS hypo-reactivity (decreased heart rate, decreased skin conductance level (SCL), and increased RSA) is thought to be associated with proactive aggression (Murray-Close et al., 2017; Puhalla & McCloskey, 2020). This autonomic under-arousal may promote stimulus-seeking and fearlessness and increase an individual’s threshold for aggression (Beauchaine et al., 2007). IPV perpetrators who displayed HR hypo-reactivity during a conflict discussion with their partners were thought to use violence, or the threat thereof, to create intimidation, force compliance, to get the partner to withdraw, retreat, or submit to their view (Gottman et al., 1995). Most research uses self-report questionnaires to classify proactive and reactive aggression (Babcock et al., 2014; Raine et al., 2006). However, Chase et al. (2001) developed a sophisticated coding system for classifying proactive and reactive IPV perpetrators based on descriptions of past violent incidents. Examining emotional differences between perpetrators coded proactive vs. reactive during observed conflict discussions, they found that men coded as reactive expressed significantly more anger and frustration during conflict with their partners than did men coded as proactive during a conflict discussion observed in the lab (Chase et al., 2001). Men coded as proactive were more domineering than were reactive perpetrators. In a replication and extension of Chase et al. (2001) study, Babcock et al. (2023) found behavioral differences proactive and reactive batterers consistent with Chase et al’s findings. In addition, based on men’s and women’s reports of men’s past violent incidents, reactive batterers exhibited greater heart rate reactivity during a conflict discussion as compared to proactive batterers (Babcock & Kini, 2023). Reactive batterers experienced increased heart rate and sympathetic arousal (i.e., flooding; Gottman, 1994) during observed arguments, suggesting intense affective arousal and difficulty regulating emotions. Proactive offenders, on the other hand, did not exhibit heightened physiological arousal. The proactive-reactive distinction is not without controversy. The typology has been criticized for its overlapping criteria and comorbidity of reactivity violence among proactive perpetrators (Bushman & Anderson, 2001). While reactive aggression frequently occurs without proactive aggression, most proactively aggressive individuals also report incidents of reactive aggression (Cornell et al., 1996). Therefore, rather than categorizing men, we coded and counted the violent incidents. As with other categorical groupings of IPV perpetrators, findings may be more powerful when testing dimensions of the characteristic, rather than assigning them into non-independent groups (Babcock et al., 2004). In the current study, we analyzed the degree of proactivity of their violent incidents rather than categorizing the men as proactive or reactive. The Proximal Change Experiment The “proximal change experiment,” developed by Gottman et al. (2005), measures changes in emotions across two conflict discussions, pre- and post- a brief communication skills-training intervention. “Micro-interventions” designed to reduce conflict within couples can be tested in the lab to evaluate whether they impact treatment targets immediately and health outcomes later (Smith Slep et al., 2023). In the Babcock et al.’s (2011) experiment, violent men were randomly assigned to one of two communication skills training exercises, ‘editing out the negative’ or ‘accepting influence’ (Gottman, 1998), or a control condition. Couples engaged in two conflict discussions interrupted by an intervention or placebo task while their facial affect and physiological responding was being recorded. Both partners completed a questionnaire after each conflict discussion assessing their thoughts and feelings about the previous conflict discussion. Overall, both communication skills training exercises led to increased positive feelings and decreased aggression. Even though the female partner did not receive the intervention, women also became less aggressive and more positive when their partners were exposed to either communication skills training technique. Although both communication skills training techniques were effective at reducing aggression, they may be differentially effective based on the degree of proactivity men’s IPV. In the Editing out the Negative technique, men are taught to substitute their immediate negative response with a more neutral one. This exercise, designed to prevent the harsh startup and break the cycle of negative reciprocity in arguments, may be particularly effective among more reactive men, due to their inability to regulate their affective and physiological hyper-arousal during conflict (Babcock et al., 2000; Chase et al., 2001; Dodge & Coie, 1987). Given that reactivity is related to negative reciprocity, we hypothesized that the Editing out the Negative would be more effective for men on the low end of proactivity. On the other hand, the Accepting Influence technique may be especially effective with men who are more proactive. The Accepting Influence exercise helps men to reframe their partner’s anger as an indication that this topic is important to them rather seeing their anger as disrespectful. They are encouraged to attend to the content of what she is saying as opposed to her tone (Babcock et al., 2011). Because proactive IPV perpetrators reject influence from their partners (Coan et al., 1997) and become aggressive when they feel disrespected or that their authority is threatened (Babcock et al., 2011; Chase et al., 2001), we hypothesized that men who are higher on the proactivity dimension would benefit particularly from to the Accepting Influence technique. Current Study The current study reexamines data from Babcock et al. (2011) proximal change experiment to discern the differential utility of the techniques between perpetrators low, moderate, or high on a spectrum of proactivity. Men who are coded as being low in proactivity (reactive) and their partners were expected to behave and report feeling less aggressively and more positively towards their partner after completing the Editing out the Negative intervention. Low proactive men were also expected to show more psychophysiological soothing (decreased HR, decreased SCL, and increased RSA) in that condition. Men coded higher on proactivity were expected to display and report more positivity and less aggression in the Accepting Influence conditions. Because proactive aggression is associated with decreased HR and SCL under stress (Bobadilla et al., 2012), high proactivity may be related to increased HR, SCL, and decreased RSA after an effective intervention – the opposite pattern of those low in proactivity. Couples were recruited for the current study as part of a larger project (N = 134) for psychophysiological responding of intimate partner abusers. Participants responded to ads seeking “couples experiencing conflict.” Inclusion criteria were that they must be married or living together as if married for at least 6 months, at least 18 years of age, and able to speak and write English proficiently. Female partners were administered the violence subscale of the Conflicts Tactics Scale-2 (CTS2; Straus et al., 1996) over the phone to determine eligibility in the study. Female partners had to report (a) at least two incidents of male-to-female aggression in the past year. Women’s violence was free to vary. A small group of distressed but non-violent couples was also recruited (n = 22). The study consisted of two data collection sessions on different days; only IPV couples who participated in both sessions and described past violent incidents were included in the current analyses (n = 81). Participants were paid $40 to $50 each for their participation. Ethics and Safety Measures The study protocol was fully approved by the Institutional Review Board, Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Committee, University of Houston and funded by the National Institutes for Mental Health. Female volunteers were informed of the nature of the experiment via telephone, before coming into the lab, and were asked not to participate if they anticipated increased risk of retribution from their partner. No deception was used, and the most sensitive questions were included in the screening and consent forms. The participants were consented and debriefed separately to assess danger potential and develop a safety plan, if needed. Both male and female participants were given a list of emotion words to assess their emotional states. Participants endorsing any negative emotions other than “feeling somewhat negative” were interviewed on their likelihood of becoming abusive. Men and women were given referrals for community resources, including counseling services, domestic violence shelters, and drug and alcohol treatment. Finally, female participants were contacted one to two weeks later by telephone to assess for subsequent physical aggression. No women reported any violence during this follow-up period. Assessment of IPV tends to predict reductions in violence over time (Gortner et al., 1997), even in studies without any intervention. Procedure Questionnaire, psychophysiological, and observational data were collected from both the male and female partners. Men participated in two sessions totaling approximately 6 hours of participation, while their female partners participated in one 3-hour session. During the second conjoint session, couples were separated to complete a questionnaire packet and then reunited for the videotaped conflict discussions. The Play-by-Play Interview (Hooven et al., 1996) was administered in order to clarify an actual conflict area in their relationship. Men were randomly assigned to receive an Editing out the Negative intervention, Accepting Influence intervention, or a control/timeout condition. Couples were then asked to sit quietly for a 4-minute eyes-open baseline, then to engage in two 7.5-minute conflict discussions interrupted by an 8-minute intervention or placebo task. The interventions involved a clinical PhD student coaching the man on how to change is communication style, then listening to listen-learn-practice (Gottman, 1998) audio recording with hypothetical situations. Briefly, Editing out the Negative focuses on being neutral or positive in response to a complaint. The Accepting Influence condition is about accepting the kernel of truth in the hypothetical complaint. The control condition was listening to music, being instructed not to think about the topic of discussion. This was conceptualized as a proxy for the “time-out” procedure, a mainstay of battering interventions (Wexler, 2000). Full descriptions of the three intervention conditions with examples can be found in Babcock et al. (2011). As a “manipulation check”, men in the two active conditions articulated aloud practice responses reflecting Editing out the Negative or Accepting Influence. These articulations were graded by trained coders to ensure that participants were attending to and able to apply the lessons. Both partners were asked to complete a questionnaire about their feelings after each conflict discussion. Subsequently, couples were interviewed separately about their history of domestic violence. During this interview, they were asked to describe in a step-by-step way two past violent incidents where the man was violent towards the woman (Jacobson et al., 1994). Both men and women were asked to describe the worst and the most recent incident of IPV. Participants were debriefed and evaluated for safety. Follow-up phone calls made one week later to the female partner assessed for any untoward events caused by participating in the project. No participants reported any subsequent violence. Measures Conflict Tactics Scale-2 (CTS-2) The CTS-2 (Straus et al., 1996) is considered the gold standard to assess for domestically violent behavior within the past year. The CTS-2 is a 78-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the severity and frequency of physical, sexual, and psychological abuse committed by intimate partners. Five scales measure negotiation, psychological aggression, physical assault, sexual coercion, and injury. Internal consistencies on the CTS-2 ranged from .49 to .78. Only male and female reports of the frequency of men’s perpetration of violence on the physical assault scale were reported here. Proactive-reactive Coding System Participants were individually administered a semi-structured clinical interview to assess their relationship and violence history (developed by Jacobson et al., 1994). As part of this interview, male and female participants were asked separately to describe the most recent and the worst violent incident in which male-to-female physical aggression occurred in their current relationship. The system used to code these narratives (Chase et al., 2001) was based on two main dimensions: 1) intentionality vs. impulsivity and 2) heightened affective arousal vs. calmness during and after a conflict. Proactive is intentionality and low affective arousal; reactive is impulsivity and high affective arousal. For the incident to be coded as proactive, meeting any of the roactive criteria was sufficient to label the incident as being proactive. In order for the incident to be coded as reactive, the incident had to meet the reactive criteria, without exhibiting any signs of proactive behavior (Babcock & Kini, 2023; Chase et al., 2001). In this study, proactivity was examined on a continuum: if neither incident evidenced proactivity, it was coded a 0; if one incident, was coded as 1; if both incidents were coded as proactivity, proactivity was scored as 2. Men were more likely to deny that any male-to-female violence had occurred than were women, resulting in fewer incident descriptions by men. Therefore, in the current study, only women’s coded descriptions of past violent incidents were entered into analysis. Play-by-play Interview Prior to discussing any conflict, a 4-minute resting psychological baselines was collected. Then the Play-by-Play Interview (Hooven et al., 1996) was administered to each couple to determine two areas of conflict in their relationship. The interview helps couples identify areas of disagreement in their marriage. Couples independently ranked how much difficulty they experienced across 10 areas common to marital discord, on a scale of 0 to 100, using a modified Knox (1971) Problem Solving Inventory. After clarifying two topics of discussion, couples were asked to sit quietly for the second 4-minute baseline, then to start to discuss the topics. After 7.5 minutes, a graduate student interrupted the discussion. While the female partner listened to music on headphones, the graduate student administered one of the brief interventions or the control condition to the man. If randomly assigned to receive the control/time-out condition, he listened to music with instructions to relax. Specific Affect Coding System The two 7.5-minute conflict discussions were videotaped and coded later by a team of 10 trained coders using the Specific Affect Coding System (SPAFF; Gottman et al.,1996). Coders were blind to condition and had to achieve an inter-rater reliability κ of .70 or higher on a series of test tapes coded by a trained graduate student reliability coder. Kappas were checked periodically over the 8 months of coding to make sure that reliability remained consistent. Weekly meetings were held to review SPAFF and discuss any problems or questions arising from coding. The conflict discussions were coded using the Video Coding Station (Long, 1998), which allows data entry synchronized with the video time code. Twenty-five percent of the tapes were coded by a second coder to calculate reliability. SPAFF categorizes 16 emotions based on facial affect, vocal tone, body language, and content of speech. For the current study, SPAFF codes were collapsed into verbal aggression and positive categories. Four codes—belligerence, contempt, domineering, and disgust—were combined into a global verbal aggression category, κ = .91. The positive SPAFF codes of validation, humor, interest, affection, and joy were summed into one global positive category, κ = .92. The neutral code and low-level negative codes (anger, stonewalling, tension/fear, sadness, defensiveness, whining) were not analyzed in this study. Psychophysiological Measures of Autonomic Nervous System Activity During two baseline measurements and two conflict discussion tasks, heart rate (HR), skin conductance level (SCL), and respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) were continually recorded using the James-Long five-channel bio-amp (Long, 1998a). Heart rate was measured by placing two pre-gelled, 30-mm square Unitrace, alligator-clip-type electrodes on the participant’s chest and a third on the sternum as a ground. R-waves were automatically detected by using the interbeat interval (IBI) data analysis program (Long, 1998b). Second-by-second heart rate (in beats per minute) was computed from the resultant IBI file. An increase in heart rate generally indicates increased arousal, caused by alpha- and beta-adrenergic activation or by parasympathetic (vagal) inhibition. Skin conductance level was measured via two electrodes placed on the volar surfaces on the distal phalanges of the first and third fingers of the non-dominant hand. Ag/AgCl electrodes (1-cm diameter) were filled with an isotonic solution and attached with double sided adhesive collars with 1-cm diameter holes and Velcro straps. Skin conductance reactivity assesses electrodermal activity, or changes in the secretion of sweat glands. These sweat levels are thought to change in response to emotional stimuli (as opposed to temperature) (Gottman et al., 1995). Skin conductance is a relatively pure index of sympathetic activation, as the sweat glands are innervated by the sympathetic nervous system. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) values were calculated using the James long software Inter-Beat Interval analysis software. RSA was calculated by subtracting the highest interbeat interval (IBI) value during expiration from the lowest IBI value for each respiration cycle (Grossman, 1983; Grossman et al., 1991). RSA is an index of parasympathetic activation, as stimulation of the vagus nerve dampens cortisol responses, inhibits the sympathetic nervous system, and decreases heart rate. Self-Reported Affect A project-designed, 36-item Likert-type scale entitled “About That Discussion” (ATD; Babcock et al., 2011) was administered to both men and women after each 7.5-minute discussion. This project-designed scale assesses self-report and collateral report of negative and positive feelings about the previous discussion. The ATD questionnaire was given to the couple twice to assess change in self-reported affect as a result of the experimental manipulations. The positive scale was comprised of five items: affection, in-control, happy, interested, and joyous. The aggressive scale was comprised of four items: angry, disgusted, jealous, and vengeful. Items about sadness, fear, worry, and hurt were excluded. All items were rated about current feelings, on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 5 (a great deal). The two scales derived from this measure showed adequate internal consistency: self-reported positive affect, α = .77, self-reported negative affect, α = .82. Articulation Skill As a manipulation check, men’s ability to learn the two techniques was coded during their articulated response to the audiotaped relationship problems (Babcock et al., 2011). During the skills training, men listened to three hypothetical situations, then articulated aloud a response that was to demonstrate either Editing out the Negative or Accepting Influence. Videotaped articulations were coded by research assistants using a project-designed coding system. Each articulation was coded by two undergraduate research assistants with a graduate student also coding 20% of the videos for reliability purposes. There were 11 items (articulation was on topic, positive in tone, soft, socially skillful, etc.) and were scored on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = disagree strongly, 2 = disagree, 3 = disagree slightly, 4 = agree slightly, 5 = agree somewhat, 6 = agree strongly). The total score of “articulation skill” was calculated by summing these 11 items and averaging across raters. Internal consistency of this rating scale was α = .83. Data Analytic Plan All analyses were conducted in SPSS version 28.0. Initial analyses present demographics and compared men’s versus women’s responses using t-tests and chi-squares. Men’s articulation skill during the practice aloud section of the active interventions was examined using correlations and Hayes (2022) PROCESS version 4.1 macro simple moderator Model 1. Correlations between proactivity and the variables of interest examined possible confounds for which to control in the subsequent multiple regression models. Seven PROCESS macro Model xxx1 moderation analyses were conducted testing intervention condition on seven outcome variables: men’s self-reported positive and negative feelings, men’s observed positive and aggressive behavior, and men’s change in heart rate, skin conductance, and RSA. The relation between the multi-categorical independent variable (X) of treatment condition (0 = control, 1 = Accepting Influence 2 = Editing out the Negative) and the seven continuous emotional outcomes (Y) was hypothesized to be moderated by proactivity (W) coded as a continuous scale (0, 1, 2). See Figure 1. Outcomes were men’s emotional responses during the second conflict discussion (T2), controlling for men’s emotional responses in the initial conflict discussion (T1) as a covariate, as was done by Probst et al., (2017). Of the 113 IPV couples recruited 81 couples completed the intervention exercises as well as the interview used to code the proactivity of the two violent incidents. Men’s average age was 32 (SD = 10.2), while women’s average age was 30 (9.37). Their mean family income as reported by men was approximately $28,000 per year (SD =39,524.73) and as reported by women was approximately $31,000 per year (SD= 26,664.23). One-quarter of the men did not graduate from high school and 12% were college graduates. Approximately 63% of the men were African American, 20% were Caucasian, 14% were Hispanic, and 3% were from other racial or ethnic origins. Average length of the relationship was 4.15 years (SD = 3.38). The sample was high on frequency of men’s physical assault. Men reported their own frequency of physical assault perpetration as averaging 14.27 (SD = 26.6) over the past year. Women reported men as perpetrating an average of 16.24 (SD = 23. 05) physically violent acts in the past year. A total of 76 women described two codable past male-to-female violent incidents with 47.4% reporting both incidents as being reactive (proactivity score = 0), 30.3% as one reactive and one proactive (proactivity score = 1), and 22.4% both proactive (proactivity score = 2). For the men’s descriptions, 75 generated shorter but codable violent incident descriptions, with a restricted range on proactivity. Only 4% of men described two proactively violent incidents. Therefore, women’s scored reports of violent incidents were entered into analysis. Correlations between the proactivity scores and demographic variables revealed significant relations between proactivity and men’s age (r = .28, p = .02). Older men were more likely to score higher on proactivity. Frequency of men’s physical assault in the past year was also related to proactivity scores, r = .443, p < .001 based on women’s reports, and r = .218, p = .04 based on men’s reports. Men’s self-report of perpetration of physical assault was highly correlated with his ability to learn and apply the communication technique during the practice period, r = -.46, p = .002, but unrelated to level of proactivity, r = -.06, p = .35. Baseline means and intercorrelations between the variables of interest are presented in Table 1. Table 1 Means, SD and Correlations with Baseline Variables and Proactivity, Ability to Learn Skills, and IPV Frequency.   Note. 1CTS-2 physical assault scale; 2Self-reported feelings on ATD scale after the first conflict discussion; 3SPAFF seconds spent displaying aggression during first conflict discussion. **p < .01 (1-tailed). The skill rating of the men’s practice articulations during the Editing Out the Negative and the Accepting Influence training were examined so that any differences found on emotion change by level of proactivity would not be attributed to solely to differential learning of the skills. First, PROCESS was used to test proactivity as a moderator of men’s ability to learn the two communication skills as a manipulation check. Men’s coded articulation skill scores during the Editing out the Negative and the Accepting Influence trainings were used as dependent variables (Y). Entering only the two active conditions (controls did not articulate) as the independent variable (X), this regression indicated, the overall model summary was not significant, R2 = .10, F(3, 44) = 1.61, p = .20. However, there was a borderline significant interaction between the treatment conditions and proactivity on men’s skill in the practice articulations in the two active treatments (b coeff. = 6.06, SE = 2.95, t = 2.05, p = .05). That is, the degree of men’s proactivity of violence appeared to moderate their ability to learn the two exercises. This interaction is explained graphically in Figure 2. Men whose violence was coded as being highly proactive performed poorly in the Accepting Influence and better on the Editing out the Negative practice exercise, although the slope of the effect of the interventions on articulation skill was not significant, b = 3.12, SE = .93, t = 0.93, p = .36. Among men who were coded as being low on proactivity (reactive), the opposite pattern was found. Low proactive men were better on mastering the Accepting Editing skills as compared to the Editing out the Negative skills, although the slopes of the impact of the interventions on articulation skill also did not meet statistical significance, b = -5.81, SE = 3.06, t = -1.90, p = .06. Using the Johnson-Neyman method, there was no transition points where proactivity predicted that the impact of the interventions on learning became significant at p < .05. Although there was a trend towards differential learning of the two skills by degree of proactivity, the pattern was not so significant as to confound the subsequent results on the emotional outcomes. In the PROCESS macro Model 1 output, the main comparisons of interest are the two conditional Proactivity x Condition interaction terms generated for each model. The multi-categorical comparison chosen was sequential so that the first interaction term represents the differences in slope comparing the control (0) to the Accepting Influence condition (1), whereas the second interaction compares slopes of the Accepting Influence condition (1) to that of the Editing out the Negative condition (2). The PROCESS regression output for the seven outcome variables is presented in Table 2. While we predicted that highly proactive men would show greater improvements in communication (more positive, less negative, less aggressive, lower heart rate) following the application of the Accepting Influence intervention as compared to the Editing out the Negative intervention, we found the opposite pattern. Self-reported Affect Model 1 revealed a significant Treatment by Proactivity interaction, F(2, 61) = 3.49, p = .04. Specifically, the moderation effect in men’s change in self-reported positive affect was significant only on the first interaction term, suggesting that the slopes between the Accepting Influence and control conditions differed significantly (t = -2.25, p = .03), whereas the slopes of the two active conditions did not differ significantly from each other (t = 1.37, ns). Figure 3 displays this interaction graphically. Probing this interaction’s conditional effects, for highly proactive men (+1 SD) assigned to the Accepting Influence condition, there was a negative relation between proactivity and positive feelings (t = -2.05, p = .05). Other slopes in Figure 3 were not significant. For self-reported negative affect, the overall model was significant, but the overall Treatment by Proactivity interaction was not, F(2, 61) = 0.24, ns. There were no corresponding moderation effects when men’s self-reported negative affect was the outcome (Table 2, Model 2). Level of proactivity did not moderate the effect of the interventions on self-reported negative feelings on the ATD scale in the second conflict discussion. Observed Affect The next set of hypotheses was related to discerning changes in observed communication during conflict following the two intervention exercises as coded by SPAFF. Model 3 tests the conditional effect of the treatment conditions on men’s displays of positive affect as coded by SPAFF during the second conflict discussion. Overall, the Treatment by Proactivity interaction was trending towards significant, F(2, 61) = 2.71, p = .07. Model 3 in Table 2 reveals that this trend was pulled by second interaction term. The Accepting Influence conditions revealed a greater conditional effect on positive emotions for the second Proactivity x Condition interaction term only, but it failed to meet significance (p = .06). Because the overall model was significant and the interaction terms were nearly significant, the interactions were explored. Figure 4 shows that highly proactive perpetrators (+1 SD) who completed the Editing Out the Negative exercise tended to display more positive emotions during the second conflict discussion than did highly proactively violent men assigned to the Accepting Influence condition. Probing the slopes, at low levels of proactivity (-1 SD) both the Accepting Influence (b = 5.57, SE = 2.32, t = 2.40, p = .02) and the Editing Out the Negative (b = 8.29, SE = 2.39, t = 3.47, p = .00) interventions significantly improved positive affect displays. At high levels of proactivity, the Editing Out the Negative exercise had a positive impact on positive affect displays (b = 13.60, SE = 4.25, t = 3.20, p = .00), whereas the Accepting Influence exercise did not ( b = 3.05, SE = 2.48, t = 1.23, p = .22), which was contrary to our hypotheses. Model 4 examines changes in men’s observed aggression following the skills-training interventions. The Editing out the Negative technique led to decreased aggression overall, whereas the Accepting Influence exercise did not. Proactivity was related to men’s baseline displayed aggression (r = .35, p < .01), and it moderated the effect of the interventions on aggression. Specifically, the second interaction term was significant (p < .001), suggesting that there was a significant difference between the two active treatments pertaining to their impact on men’s observed aggression. Figure 5 displays this interaction graphically. Examining the slopes, the Editing out the Negative was related to significantly decreased aggression (b = -14.12, SE = 5.44, t = -2.59, p = .01), whereas the Accepting Influence was not (b = -4.23, SE = 6.50, t = -0.65, p = .52). Among men coded low in proactivity, the Accepting Influence exercise lead to less aggression (b = -8.28, SE = 3.12, t = -2.66, p = .01), whereas the Editing Out the Negative exercise did not (b = -2.35, SE = 3.08, t = -0.65, p = .52), although we predicted the opposite. Table 2 Testing Proactivity as a Moderator between Treatment Condition and Change in Men’s Emotions   Note. Accept * Proactive is Interaction xxx1, comparing Accepting Influence vs. Placebo condition. Edit * Proactive is Interaction xxx2, comparing Accepting Influence vs. Editing Out the Negative condition. ***p < .001, **p < .001, * p< .05, tp < .10. Psychophysiology Finally, in examining psychophysiological changes in the second conflict discussion, there was a significant interaction with proactivity by condition in men’s heart rate only (see Table 2, Model 5). For range corrected heart rate, highly proactive men who received the Accepting Influence technique had significantly higher heart rates in the second conflict discussion as compared to highly proactive men after receiving the Editing Out the Negative technique. This interaction is displayed graphically in Figure 6. Probing the interaction, for those low in proactivity (-1 SD), there is no relation between heart rate and receiving the Accepting Influence (b = -.08, t = -1.30, p = .20) or the Editing Out the Negative conditions (b = .07, t = 1.36, p = .19). However, for those high in proactivity (+1 SD), the slopes between the Editing out the Negative were significantly negative, b = -0.1184, t = -1.99, p = .05, suggesting that, while we predicted that the Accepting Influence would be more impactful for highly proactive men, it was the Editing out the Negative exercise which was more physiologically soothing for them. The regressions testing skin conductance (Model 6) and RSA (Model 7), revealed no significant differences by condition or in slopes. The variability in T2 skin conductance and RSA was mostly accounted for by T1 skin conductance and RSA. The purpose of the current study was to evaluate the differential utility of specific communication exercises across levels of proactivity. Given that this study re-examined data from the original study (Babcock et al., 2011), we knew that overall both intervention exercises were effective in promoting positive behavioral and emotional change among IPV men and their partners. This study’s question was for whom do the communications skills training work. We predicted that high proactively violent men would respond positively to the Accepting Influence exercise while low proactive (reactive) men would respond more to the Editing Out the Negative exercise. However, we found the opposite. Among highly proactively violent men, the Accepting Influence technique appeared to make them feel worse, not better. After the Accepting Influence exercise, highly proactive men were less positive, more aggressive, and had higher heart rates as compared to highly proactive men who participated in the Editing out the Negative exercise. Highly proactive perpetrators felt even less positive after the Accepting Influence technique than did highly proactive men who took a brief time out. Overall, proactivity was unrelated to how well IPV perpetrators learned and applied the communication skills. Low proactive men (reactive) could learn and apply both communication skills in the practice sessions. Proactive men, however, tended to be less competent at articulating statements that reflected accepting influence. Perhaps the negative impact of this exercise on affect and heart rate among highly proactive perpetrators is because they struggled to learn the more abstract Accepting Influence communication skill. Alternatively, highly proactive perpetrators, who may have power and control issues, may resist adopting the Accepting Influence stance, it being contrary to their modus operandi in relationships. Men whose IPV was highly proactive fared better in the Editing Out the Negative condition. Not only was it easier to learn, but highly proactive men improved their emotional states in this condition. They displayed less aggression, reported and displayed more positive, and had lower heart rates after this intervention. This technique is more concrete than Accepting Influence, teaching men to substitute their impulsive immediate negative reaction for a neutral one. Editing out impulsive negativity may be particularly helpful for highly proactive IPV offenders who may be in the habit of using psychological abuse to assert power and control over their partners (Babcock et al., 2000; Chase et al., 2001). The Editing Out the Negative technique was also easier for highly proactive men to learn. Perpetrators who were low on proactivity could learn and apply both communication techniques. Their pattern of emotional responses suggest that reactive men do particularly well in the Accepting Influence condition, as evidenced by greater positivity, less aggression and lower heart rates. Reactive men have a tendency to be impulsive, to easily perceive threat, and are prone to escalation of negativity (Chase et al., 2001). Perhaps techniques that urge more prosocial cognitive reframing are successful in reducing the negative reciprocity so commonly seen in couples with a reactively violent partner. With regard to psychophysiological reactivity, the communication skills-training conditions revealed a differential impact on change in heart rate reactivity based on proactivity of violence. Highly proactive men experienced low heart rates following the Editing Out the Negative but high heart rates following the Accepting Influence training. Men low in proactivity showed the opposite pattern. Men in the control (listening to music) condition had high heart rates in the second conflict discussion, regardless of their levels of proactivity. Unlike the study by Thomson et al. (2021) revealing that proactivity is related to decreased skin conductance change, we found no relation between skin conductance and proactivity. However, the Thomson et al.’s study used a fear induction rather than an emotional conversation as the independent variable. Thus, the current study’s findings of differential responsivity to the two communication skill exercises depending on level of proactivity lends support for tailoring interventions specific to types of IPV perpetrators. While some scholars believe that it is a mistake to consider IPV as a reactive response as a result of frustration and arguments (Walters, 2020), in community samples, much of the IPV results from impulsive, reactive, harmful fights between partners. Communication skills, conflict resolution skills, and relationship satisfaction are consistent risk factors for both men and women’s IPV perpetration (Love et al. 2020). It is for reactive or situationally violent offenders that couples’ interventions would be most appropriate (Babcock et al., 2017). Perhaps the most surprising finding is that one of the communication skills exercises had an immediate impact on highly proactive IPV offenders’ emotions at all. Highly proactive offenders may have low empathy and a criminal thought process that perpetuates the cycle of violence, using IPV to intimidate and control their partners (Walters, 2020). Nonetheless, they, too, may benefit from concrete couples’ communication skills training. Whether reducing the negativity of the arguments among couples with a proactively violent man translates to reduced recidivism of IPV long term remains an open question. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions The strengths of this study include the design and methods. Rather than conducting expensive randomized clinical trials of a multi-technique therapy package, proximal change experiments can allow causal inferences about the immediate impact of techniques on behavioral outcomes. The PROCESS analyses emphasize the proactivity by intervention condition by time by controlling for initial levels of each outcome variable, prior to the administration of the intervention. This is preferable to testing change scores or repeated-measures MANOVA, as both methods inflate measurement and Type I error (Hayes & Little, 2018; Zinbarg et al., 2010). This study collected and coded a breadth of variables among a difficult to recruit sample. However, there were limitations of the study, the most significant of which is the small sample size. The relatively small samples make it difficult to find significant interaction by overall outcome means. Moment-to-moment analyses could avoid such power limitations. Future studies may examine ongoing changes in psychophysiological responding among partners and victims during and after verbally aggressive acts observed in the lab using more powerful multi-level modeling statistical techniques (Godfrey, 2022). Future studies could also examine the co-activation of SCL and RSA, as decreased SCL combined with increased RSA has been shown to be predictive of proactive aggression (Moore et al., 2018; Thomson et al., 2021), although co-activation may be moderated by other traits, such as emotional regulation abilities (Puhalla & McCloskey, 2020). Another limitation of this proximal change study is that we did not conduct follow-ups to assess distal changes in IPV. Although it is doubtful that an eight-minute intervention could impact behavior in the long term, future studies may examine longer interventions with longer follow-up periods. The Accepting Influence condition had null or detrimental effects on highly proactive men. Theoretically, there could be a “sleeper effect,” where the impact of the Accepting Influence intervention is not immediately apparent but reveals itself later. However, proximal change experiments are premised on the fact that there is little evidence that sleeper effects exist in psychotherapy research (Flückiger & Del Re, 2017). Moreover, because the interventions had immediate effects on behavior, they may not be the most effective way to produce long-term, sustained change. Results may not be generalizable to female perpetrators of IPV, given that there are gender differences in how proactivity affects psychophysiological responding (Thomson et al., 2021). Finally, another limitation of this study is that the communication skills interventions were only carried out with the male partners. Given that female partners may habituate to and exacerbate dysfunctional patterns of communication with their partners, both partners completing the same communication skills-training exercise may be more beneficial in improving couples’ communication long term. To date, there is very little research on the differential utility of specific intervention for different types of men who batter women. Men arrested for IPV are generally mandated to attend a one-size-fits-all battering intervention program (Babcock et al., 2004). Furthermore, although interventions have attempted to reeducate batterers about the inappropriateness of patriarchal attitudes and beliefs (the Duluth model) or modify dysfunctional thought patterns (CBT), clinicians rarely address the couples’ dysfunctional communication patterns that are implicated in violent incidents. Although it is politically challenging to implement research on couples’ interventions among court mandated IPV offenders (Babcock et al., 2017), this study provides preliminary evidence that perpetrators can learn and apply new communication skills, and, when they do, it has a positive impact on their emotions, behavior, and physiology. Teaching reactive men to accept influence from their partners and proactive men to edit out the negative tone from conversations appears to have positive short-term impacts. However, proactively violent men may have difficulty learning and applying more abstract, acceptance-based interventions. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Babcock, J. C., Kini, S., Godfrey, D. A., & Rodriguez, L. (2024). Differential treatment response of proactive and reactive partner abusive men: Results from a laboratory proximal change experiment. Psychosocial Intervention, 33(1), 43-54. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2024a2 Funding: Collection of these data was funded by the National Institutes for Mental Health R03 MH066943-01A1 and by the University of Houston. This manuscript was extracted from the master thesis and dissertation of Sheetal Kini in partial fulfillment of her Ph.D. at the University of Houston. |

Cite this article as: Babcock, J. C., Kini, S., Godfrey, D. A., and Rodriguez, L. (2024). Differential Treatment Response of Proactive and Reactive Partner Abusive Men: Results from a Laboratory Proximal Change Experiment. Psychosocial Intervention, 33(1), 43 - 54. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2024a2

Correspondence: jbabcock@uh.edu (J. C. Babcock).

Copyright © 2025. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef